Copyright : Re-publication of this article is authorised only in the following circumstances; the writer and Africa Legal are both recognised as the author and the website address www.africa-legal.com and original article link are back linked. Re-publication without both must be preauthorised by contacting editor@africa-legal.com

Kenyan Property Deals Need Expertise

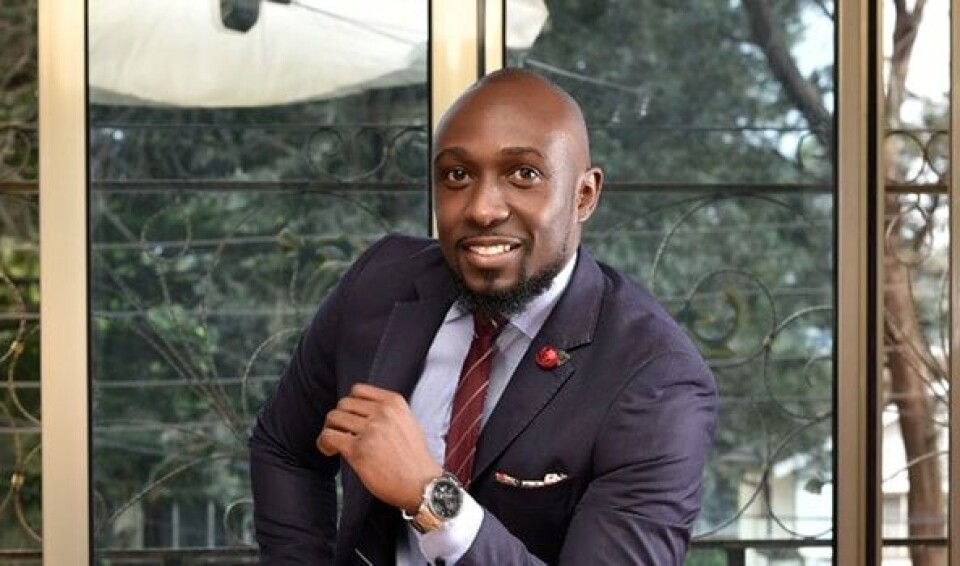

Navigating Kenya’s real estate sector, rife with fraud and bureaucracy, is not easy. But property law specialist Andiva Elvis, 31, aims to ease the process for buyers, investors and developers.

Andiva started the Adelante Group, a property consortium, in August 2017 after working for a real estate agency and realising there were gaps in the industry.

“What I saw was that you had to outsource for every profession. If you needed a legal team you had to hire a lawyer; if you needed an architect you had to hire an architect.” His dream was that anyone with a real estate project, be it a family buying a home, a foreigner looking for an investment, or a client hoping to build, should be able to find the expertise they needed in one place. Which is exactly what his company is about.

“We handle the legal side, the drawings, the quantity survey, the contractor, you name it, everything is under one roof.

Clients should see one person who advises and reports to them on every aspect of their investment. To enable my own competence I have had to research and study the different professions we accommodate,” he said.

Andiva prides himself on personal contact, saying a shortcoming of the property industry is people who do the bulk of transactions via phone or email, and then show up realising the land or property they have been sold doesn’t exist, or is not what was advertised.

He, and his associates, always visit a property, asking questions around neighbourhoods, to ensure it really is for sale or lease before they take on a client.

“There are so many court cases around fraudulent transactions because no proper due diligence is done.

“This is not like buying a loaf of bread...clients and agencies need to be informed on the importance of due diligence procedures. In fact this should form a third of the property transfer process.”

In Kenya it is not unusual for two people to provide valid title deeds for the same land, or for permission to be granted to build in an area that never should have been approved by the requisite environmental and government agency, he explained.

In 2018, the national environmental watchdog, NEMA, tore down buildings that had been constructed on riparian land. Andiva said he had advised one client against buying property in an apartment block near a water source after finding out that the developer did not have the construction approval from the Water Resources Authority.

“A client needs to know and must be informed about all the governmental and environment bodies that a developer or seller needs to have sought consent, permits and licenses from before seeking transfer of the property.

Andiva grew up in Kitale in Kenya’s Rift Valley, and moved to Nairobi as a teenager, but found it too fast-paced and unfriendly for his liking.

However, once he started working and later when he started his business, he found that his outgoing nature and tendency to greet everyone, more suited to the countryside, was a boon and appreciated by clients.

After finishing at the Kenya School of Law, he started his pupilage working in the employment, labour and patent law departments of a city law firm.

“But I was not in love with the slow court procedures and bewildering registry lines that we had to labour through as pupils to get served.”

When a conveyancing instruction was given to him to handle, it became the genesis for his new found purpose with property law.

“It’s procedural, yes, but the fun is the nitty-gritty where you have to tailor a transaction to suit a client’s specific needs. For instance, you might find a property has an inheritance issue and you have to merge property law and family law into one to get the desired result.”

“What hinders property law practice is that we do not have many specialist advocates in Kenya. Most advocates are practising everything in law.”

Andiva said 80 percent of his clientele were foreigners looking to invest.

In recent years the prices of land, construction materials and property have skyrocketed in Nairobi, with an oversupply of luxury properties and few affordable options for the emerging middle class.

However, he said, developers were looking to work with the government on affordable housing projects which would balance the market and drive prices down.

Residential developers could currently see returns of 8 to 20 percent while the commercial or hotel developers could get about 5 to 15 percent.

The market was expected to do better in 2019 and 2020 before the expected slump ahead of the next electioneering period.