Copyright : Re-publication of this article is authorised only in the following circumstances; the writer and Africa Legal are both recognised as the author and the website address www.africa-legal.com and original article link are back linked. Re-publication without both must be preauthorised by contacting editor@africa-legal.com

Humaneness Must Guide Evictions says Ugandan judge

More than two decades after the Constitution came into effect in Uganda, a judge has put the government on terms to develop guidelines for rampant evictions in the country. Tania Broughton reports.

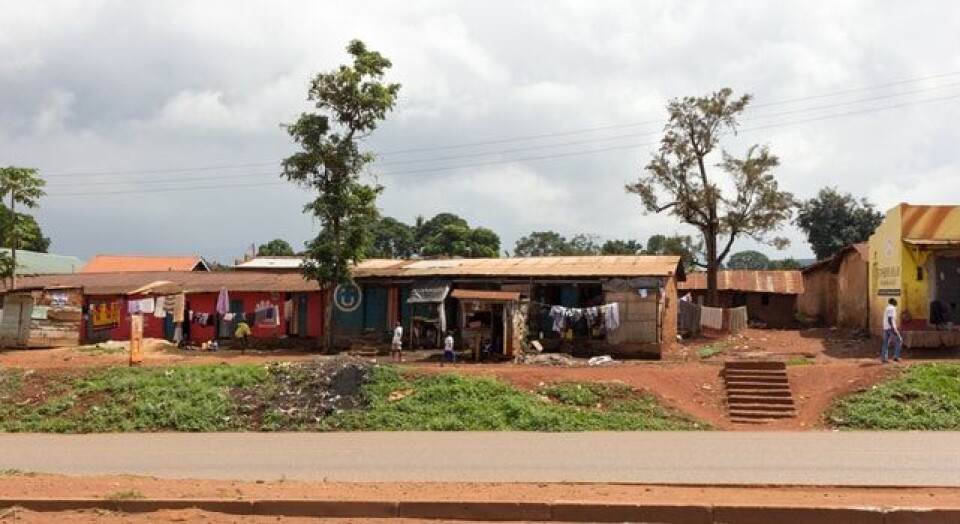

The case before Kampala-based Justice Musa Ssekaana was launched by a group of landless people who all described how they had been “violently” evicted, with little notice and with no compensation, from their homes and land.

According to expert evidence, forceful evictions - to allow for government or private development - are common place.

The group complained of loss of property, inhumane degrading treatment and loss of livelihoods.

One, Kiberu Ali, said he and others were chased off their land when the Uganda Railway needed it for development.

“Houses were demolished. Tear gas was used, people died. There was no time to save property.

“Families scattered and even the school was demolished,” he said in his affidavit.

Several expert witnesses also testified in the “public interest” case.

“They said there were no regulations and guidelines. There was no “open policy”, no consent from communities,” Judge Ssekaana said.

“They said while some evictions are justified, they must be carried out in a manner warranted by law.”

In an opposing affidavit, Josephine Kiyingi, of Attorney General Chambers, said the issues raised were capable of being resolved in private suit against the government.

She said there were “safety legal guarantees” for aggrieved persons.

The judge took the opposite view.

“Evictions normally result in severe human rights violations, particularly when they are accompanied by use of force. The victims of the forced evictions are put in life and health threatening situations and often lose access to food, education, healthcare and other livelihood opportunities.

“Forced evictions often result in losing the means to produce or otherwise acquire food or in children’s schooling being interrupted or completely stopped….people are pushed into extreme poverty.”

He said it was the duty of the State to bridge the gap between the “haves” and “have nots” in society to avoid situations where people who live in intolerable conditions are not tempted to invade the lands of others.

“The government is under a duty, not only to protect property, but also to take proactive steps to ensure that social and economic rights of the people are given meaning and not to merely to adopt a position of non-interference.

“In my view, where the State allows people to occupy land - be it government or private - for a considerable period of time so that the people consider the said land to be their homes, it would be inhuman for the State or the private developer to suddenly evict them forcefully without affording them an opportunity to seek alternative mode of accommodation/decent shelter.”

He said land grabbers must equally be discouraged to avoid lawlessness.

The judge ruled the absence of adequate procedure governing evictions was threat to, and could lead to, violation of the right to life, right to dignity and the right to property.

He ordered the Government to develop comprehensive guidelines governing land evictions and said, “due to the gravity of the consequences resulting from the absence of such guidelines from a human rights perspective” the government must report back on progress within seven months.