Copyright : Re-publication of this article is authorised only in the following circumstances; the writer and Africa Legal are both recognised as the author and the website address www.africa-legal.com and original article link are back linked. Re-publication without both must be preauthorised by contacting editor@africa-legal.com

Dream of Law Almost Ended by Dyslexia

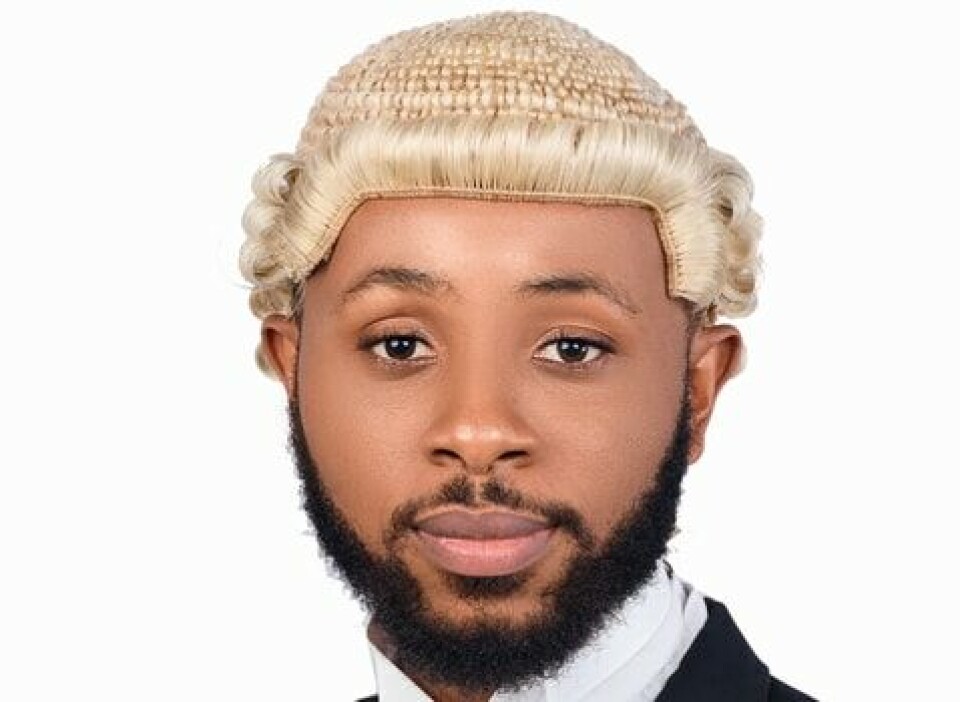

Nigerian lawyer Edwin Ugwuodo speaks to Africa Legal’s Ugochukwu Kingsley Ani about coming to terms with his dyslexia - a hurdle that almost killed his dreams.

Throughout his studies at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka and then at the Nigerian Law School in Lagos, Edwin knew something was wrong. But now, after finally being diagnosed with dyslexia last year, he has joined Dyslexia Nigeria as an associate and is working to create awareness of a common learning difficulty that undermined his self-confidence and made him question his intelligence.

When did you discover that you had dyslexia?

I had suspected it for some time but, when I was working on my final year project at university in 2015 I read up on it and knew this was what I had. Last year I had a proper assessment by Dyslexia Nigeria in Ikeja and was given a definite diagnosis.

Can you tell us about what you’ve had to overcome - given your learning disability?

It’s a lot, actually. I find it difficult to write; during my school days I had no good notes in class because even I couldn’t make sense of what I had written.

I had to rely on my friends’ notes. I really struggled even though I made a lot of effort. The lecturers at university were impatient and criticized my learning ability; it was as if I knew nothing I was taught. I didn’t have the opportunity or time to learn at my own pace.

How did you cope given that the educational system in Nigeria doesn’t consider people’s individual differences and unique circumstances?

Those working in the system don’t know anything about dyslexia. There is a standardized system of learning which won’t change. I am not criticizing this system, because many have passed through it and done very well. However, for the few of us with learning disabilities, it is tough because we are caught up in a system that doesn’t make provisions for us.

We’re taught based on how they want us to understand, not how we’re wired to understand. Some-the lecturers-give you notes and expect you to give it back to them exactly the way they gave it to you. I found this extremely tough.

What points in your life were the most difficult?

It has been pretty tough all the way through. I spent my school days thinking that I couldn’t make it. I found it difficult to read. At university, most people read to pass well - I read hard just to pass my exams. Many tried to help me but, the more they tried the worse I became. But, during all this, I discovered what I was good at: socials, leadership. I used this to cover up my deficiencies.

What was the critical moment when you decided not to be beaten?

It was during my third year at university. I was in love with the Law. I told myself that I must fight. I mean, what would my family and friends say? The stigma of what they would think or say made quitting unthinkable. Furthermore, many of my friends encouraged me greatly and I pushed with everything I had.

Then my internship with KPMG steeled my resolve. My school team won the National Tax Competition and interning with KPMG was one of the prizes. At KPMG I met many extremely intelligent and driven people. When my three-month internship drew to a close, I wrote a story and shared it online. It went viral; KPMG staff read the story and circulated it among themselves. So many people shared it online. It was a defining moment. KPMG helped build a foundation for me; with that I realized that I could be all I wanted. I couldn’t give up then.

Given your disability, how do you think Nigeria’s educational system can be improved?

They should make the lecturing pattern flexible to accommodate students who cannot cope. Personally, I can’t cope with the long hours we spend in lecture classes. Long lecture hours left me mentally exhausted.

In England they have the Equity Act (2010) preventing any discrimination against people with disabilities. We need this in Nigeria.

You are an associate working with Dyslexia Nigeria. Could you speak this work?

The awareness campaigns I am involved in show that our educational system doesn’t give room to understand dyslexia and other learning disabilities. Parents, teachers, siblings all think this is a spiritual issue. I am passionate about this, but I am helpless as I can only do so much. The government and the educational system should do more to actively understand and measure learning disabilities. That way, they’ll know what they are dealing with and how to handle it.