Copyright : Re-publication of this article is authorised only in the following circumstances; the writer and Africa Legal are both recognised as the author and the website address www.africa-legal.com and original article link are back linked. Re-publication without both must be preauthorised by contacting editor@africa-legal.com

Blazing a Path for LGBT Rights in Kenya

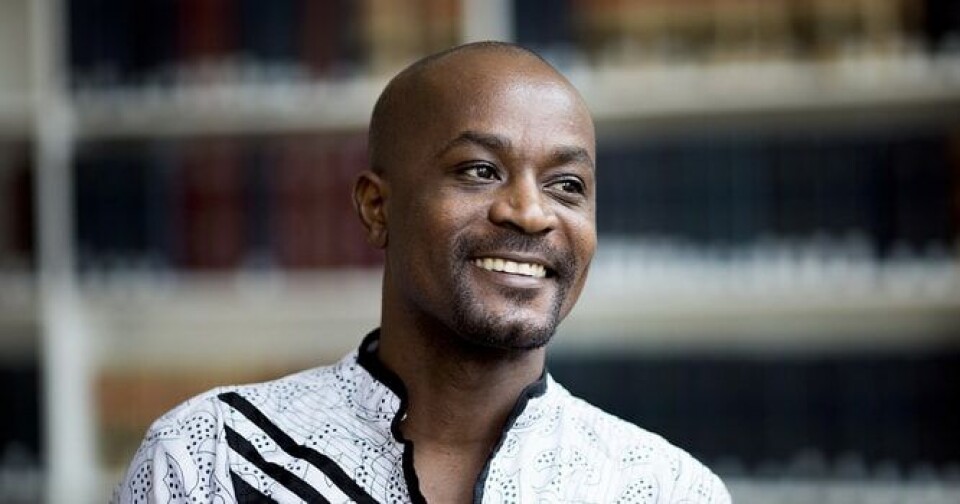

Lawyer Eric Gitari is working to end discrimination against the gay community in Kenya by changing the law. He spoke to Africa Legal.

When Kenyan lawyer Eric Gitari, 34, realised he was gay, he didn’t have the vocabulary to describe his sexuality and who he was.

But very quickly the taunts, nicknames and bullying he endured in high-school gave way to a greater realisation that, in the eyes of Kenyan society, he had no respectability, no legal equality, and could end up in prison for up to 14 years merely for his sexual orientation.

Gitari is now one of several gay rights activists leading a petition to decriminalise homosexuality in Kenya, which the High Court was set to rule on on February 22 but which has been postponed to May 24.

The co-founder of the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (NGLHRC) grew up in rural Meru, in eastern Kenya, as part of a community where religious leaders known as Mugawe were once revered, even though scholars say they dressed as women and were often homosexual.

“My grandma told me about them and how useful they were. But my father (educated by missionaries) said Mugawes were wizards,” Gitari said.

This is the story of homosexuality in Africa, a practice history shows had been at least tolerated in many communities before the advent of missionaries, colonialism, and governments decrying it as an unacceptable Western import.

Gitari recalls a childhood buried deep in books, with a curiosity about the world that already led him to question things like “why girls or women have to be at a lower status than men”.

It was this inquisitiveness that led him to study law, against the wishes of his parents who wanted him to be a doctor.

After law school he joined a prestigious law firm, but quickly realised he was not happy, and quit to go and “find himself”.

This saw him bouncing around, teaching at a juvenile prison, writing stories, living as a nomad and hitchhiking across east Africa.

“I hitchhiked in Kenya, at some point I went to Somalia and at some point I went to Uganda, I tried crossing to the Democratic Republic of Congo, that’s when my hitchhiking ended, I was broken by conflict, I was going to troubled areas.

“Seeing how law and order had broken down got me back to my senses as a lawyer.”

Upon his return to Kenya he volunteered with an organisation dealing with gender-based violence before getting a job at the Kenya Human Rights Commission in charge of setting up their LGBT programme.

He noticed anti-gay sentiment worsening on the continent, with Nigeria and Uganda pushing stricter legislation, the 2011 murder of a prominent anti-gay rights activist in Uganda, and rumblings of an anti-homosexuality bill in Kenya.

“That’s when I said we are not going to have any of this nonsense, there is the option of fighting with fire, or trying to make a building fireproof. We set about trying to make Kenya fireproof.”

In 2012, he and five other advocates set up the NGLHRC to fight for legal reforms and create a civic space for LGBT individuals.

In a major victory for Kenya’s LGBT community, the organisation in 2018 won a case to ban forced anal testing, which had long been used on men suspected of homosexuality.

But it is two sections of the penal code which allowed such practices to take place, and which petitioners now want struck down. These sections make consensual sex between adults, that are considered “against the order of nature”, punishable by up to 14 years in jail. While the law is largely unenforced, it allows for state-sanctioned persecution, activists say.

Those who suffer blackmail, violence and discrimination are unable to seek justice by virtue of being considered criminals themselves.

To Gitari, changing the laws are a way to slowly change society.

“Without legal justice, social justice takes a lot longer … There are people who are saying that we should first win hearts and minds before we change the law, in my opinion it is not either or we can engage in both processes at the same time.”

He said that as other African nations grapple with their own anti-gay laws, Kenya has a chance to set an important precedent.

Gitari is currently working on his PHD at Harvard University in the United States, and is researching the criminalisation of homosexuality on the continent.