Copyright : Re-publication of this article is authorised only in the following circumstances; the writer and Africa Legal are both recognised as the author and the website address www.africa-legal.com and original article link are back linked. Re-publication without both must be preauthorised by contacting editor@africa-legal.com

We Share Everything

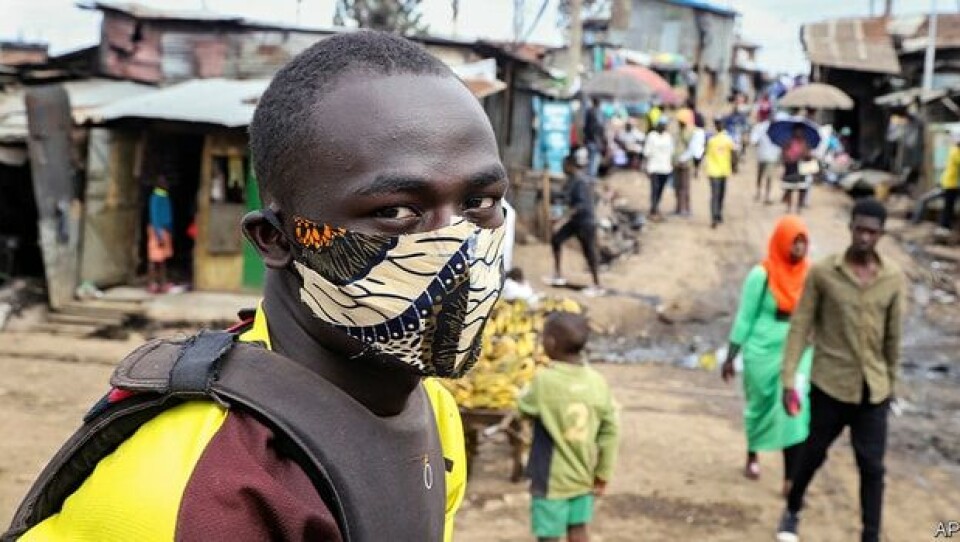

Siboniso Mngadi knows the townships of the South African coastal city, Durban, intimately. The residents of these sprawling shack settlements, where social distancing is impossible, are among the world’s most vulnerable facing the deadly Covid-19, he says.

In a settlement where the survival of one is dependent on another, adhering to a “social distance” and self-isolation is an unattainable luxury even if it is the only way to stop Covid-19.

Amid the 21-day national lockdown, declared by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa to curb the widespread Covid-19, I felt the pain endured by millions of fellow South Africans who lived in the squalor and overcrowded townships and informal settlements.

They are vulnerable. It is a matter of time before one of them gets infected and the virus runs rampant.

Having lived in a township, I could never have imagined a day without leaving the house. Hanging out on a street corner with my peers was the coolest thing about the township life.

We would mockingly banter about everything - our imaginary mansion in the suburbs and glorious careers we hoped for. It was everyone's dream to escape township life.

As Covid-19 surges, keeping a one-meter distance would be great as a precautionary measure, however, in a township, the same distance is barely the space that separates neighbours.

I paid a visit to KwaMashu. It is one of the oldest and most historic townships in South Africa, located 20 km north of Durban.

The township boasts hostels and informal settlements, where most Zulu people, who hail from the deep rural areas of KwaZulu-Natal, settle when they come to Durban in search of a better life.

Although some have migrated to city life, the Zulu culture, values and customs are deeply ingrained. The Nazareth Baptist Church remains dominant.

Almost every weekend there is a traditional ceremony, maybe small or big, where it's hard to limit the guests as the entire ‘hood’ is invited in Zulu culture.

But the streets were unusually quiet for my visit as police and members of the National Defence Force patrolled the ‘location’.

On an ordinary day, you would not walk this ‘freely’ in a township.

As I navigated through the small streets, I felt the sense of ‘lockdown’. There was nobody about.

But although many were not on the streets, they could be spotted gathered next to their tiny houses, chatting, some even having alcohol, which is temporarily banned.

In a township set-up, neighbours are a few metres apart and most houses are not fenced off. In the hostels (built by the apartheid state to house African migrant workers - mainly men), due to the ever-increasing population, some have built informal shelters inside the precincts.

Showers, toilets and water taps are communal in some sections which makes people even more vulnerable to the virus.

As I walked through, a frail, elderly woman sat quietly under a tree next to her house. As I approached her two more joined, we had a group chat.

From our conversation, I could hear they understood the virus is deadly but they remained unfazed.

They were grateful for the police presence, mainly because crime and drug use are out of control in the area.

However, I felt that there was a lack of information about how the virus is transmitted from one person to another.

“We have been told not to go out because of the virus. But here we share a lot of things; we have to check on each other as old people,” said one lady in her 60s.

I fear that as the number of confirmed cases is on the rise, a disaster is looming for the people of the townships where privacy is a luxury and every basic service is shared.

To join Africa Legal's mailing list please click here