Copyright : Re-publication of this article is authorised only in the following circumstances; the writer and Africa Legal are both recognised as the author and the website address www.africa-legal.com and original article link are back linked. Re-publication without both must be preauthorised by contacting editor@africa-legal.com

Switching off Mute

Africans are adapting their lives to fit around Covid-19 but questioning if they are happy with the way society is structured and if this pandemic has provided an opportunity for change. Ifeoluwa Ogunbufunmi reports.

In his 2020 newsletter, Professor Wale Adebanwi, the Director of the African Studies Centre at the University of Oxford, said that in this unprecedented era, every academic discipline was being forced to rethink “not only the conditions of our morbidity and mortality, but also the overarching questions of what it means to be human under exceptional conditions of vulnerability”.

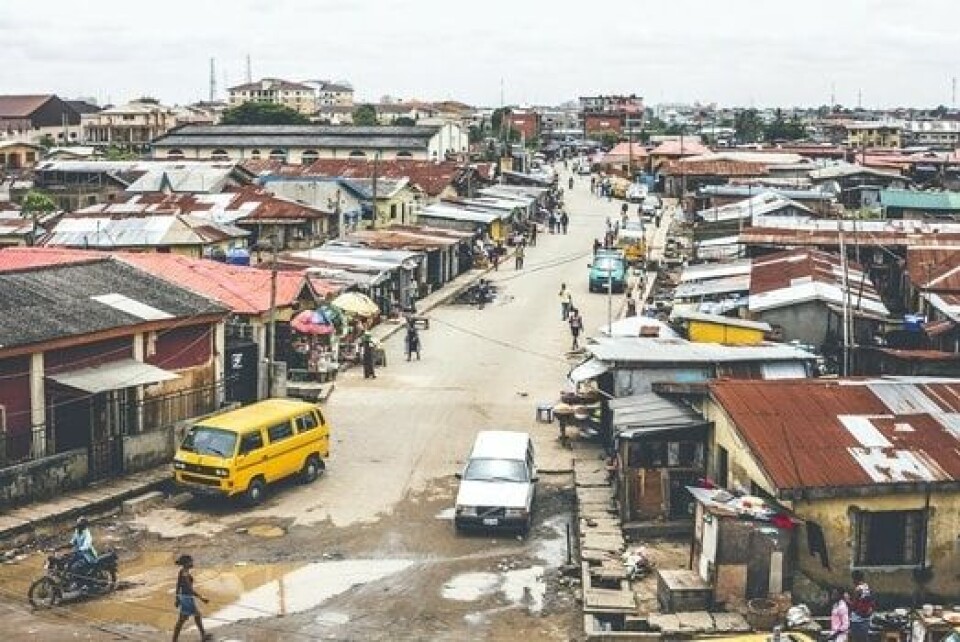

As a young African living and working in Lagos, the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic was terrifying. Lagos is one of the world’s most populous cities (est 20million) and wheeling and dealing and then, afterhours, partying and socialising, is at the very core of every life.

Would Covid destroy exactly what it meant to be Nigerian, and African?

Unsurprisingly, we have all adapted. And, while social distancing might not be as rigorously adhered to as in other parts of the world, we, as Africans are finding a new way of being.

Olusola Adewole, an Advisory Associate Director (People & Organisation) at PwC Nigeria, says the push for business is to enhance the digital fitness of the workforce and shift towards a more digital culture.

“What if investing in a more digital workforce and culture offers the greatest enabler for innovation and growth?”

Professor Lai Oso, a lecturer at the Lagos State University, says the pandemic could be the impetus for improving infrastructure.

"In Nigeria, the poor internet infrastructure has meant that students are finding it difficult to undertake academic work remotely, including the use of virtual libraries, which are indeed absent in most Nigerian universities.”

Will these changing needs and shifting priorities be a driver for social change?

Dr Liz Fouksman, the Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at Oxford University, writing in the African Studies Centre newsletter, says, “the global coronavirus pandemic has turned the insistence that only the hardworking deserve money on its head.”

She says that now governments insist, often against the wishes of citizens, that people must not go to work.

“The only way that they can do so is to give cash to people who are not working – precisely the policy that many have long feared would lead to laziness and moral and economic decay.”

She also points out that it has also become clear that the work that remains essential to keep society running (the work done by bus drivers, postal workers, delivery drivers, supermarkets cashiers, rubbish collectors) is some of the lowest paid, and is often outsourced, short-term and unstable.

“The link between how essential or socially valuable a job is and how well compensated it is by the labour market clearly does not hold.”

Will this mean that we relook at the way we organise our human system? Will that businesswoman in her flashy outfit and designer bag become redundant as we reform a new social order?

In Nigeria, like the rest of the world we have shifted to our “new normal” adapted to a virtual world, accepted that we need to wear face coverings and try as we might, to keep our distance.

Here too, we watch as the number of positive cases creep up and the death toll gradually rises.

Where will this all end? In the words of my countryman Professor Adebanwi, what is most important now, “under these conditions, we must reaffirm the value of our collective and individual lives….” and what it means to be human.

To join Africa Legal's mailing list please click here