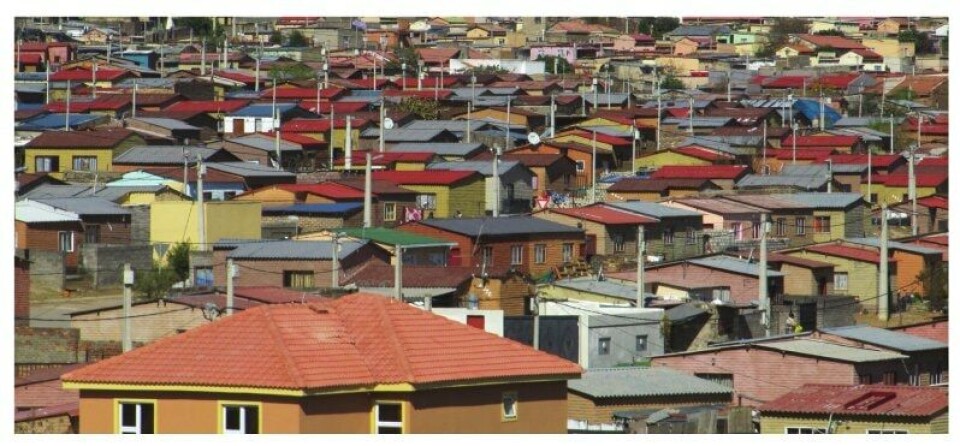

In both Johannesburg and Cape Town the media have reported on the violent protests by poor communities in relation to the lack of services delivery in relation to housing. These protests have been violent and caused considerable disruption in the two cities.

Section 17 of the Constitution provides that ‘everyone has the right, peacefully and unarmed, to picket and to present petitions’. In an important judgment by High Court in Acting Superintendent - General of Education of Kwazulu-Natal v Ngubo it was held that this right to assemble and demonstrate implicitly extended no further than what was necessary to convey the demonstrators’ message. The court also held that it was not possible to conceive of any situation where the right to assemble and demonstrate could be so extensive as to justify harassment, delicts or criminal acts. Democracy must be clearly distinguished from conduct that constitutes mob rule. From the above explanation it is categorically clear that violent service delivery protests as have recently occurred in the cities of Johannesburg and Cape Town are unlawful and unconstitutional.

Although such violent protests cannot be condoned, it is necessary to ask why they are occurring and what should be done in response to them. It appears that these communities are intensely frustrated by lack of service delivery and regard violent action as the only way to communicate with the relevant political authorities about their pitiful plight of homelessness and extreme poverty.

Section 26 of the Constitution provides inter alia with ‘the right to have access to adequate housing’. This socio-economic right is however qualified in that section 26(2) stipulates that ‘the state must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of this right’. In the famous Grootboom case the Constitutional Court found that this right is justiciable or can be tested. This means that the executive can indeed be held accountable. It is not merely the metaphorical ‘paper tiger’ and that the courts have the power to determine whether the action of the relevant executive authority had indeed acted in a reasonable manner. From this case the criterion of reasonableness was formulated and applied to other situations involving socio-economic rights such as with the right to health care, as set out in Section 27 of the Constitution.

South Africa has one of the most progressive constitutions and Bill of Rights in the world, involving first, second and third generation rights. First generation rights are the civil and political rights, like freedom of expression and religion and universal franchise. Second generation rights are those rights having a socio-economic content, such as access to housing and health. Third generation rights involve those relating to the environment and development.

The second generation or socio-economic rights require the state to provide the community with basic services. De facto this does not depend only on finances and resources, but on the capacity of the state, be it at the local, provincial or national sphere of government to use and apply the available resources. Very often funds are indeed available for instance for housing, but not actual utilized because of lack of capacity and returned unspent to the treasury. This indeed has occurred in Gauteng and elsewhere.

This lack of capacity is reflected in a report in The Mercury ‘Matric shock for KZN councillors’ (4 May 2018), where the MEC for Co-operative Governance state that ‘more than 200 councillors across KwaZulu-Natal do not have matric’. She went on to state also that ‘to date, we have made decisions nullifying seven full-time applications and 33 acting applications for appointment of municipal managers not qualifying in municipalities. The lack of service delivery is also exacerbated by corruption and cadre deployment.

The practice of cadre deployment, whereby persons who are card carrying members of the ANC have been appointed to positions in the public service regardless of their competence, is in most cases unconstitutional and unlawful. This was held to be the position in an important case in an Eastern Cape High Court judgment in Mlokoti v Amatole District Municipality of 2008, in which the judge declared unequivocally that cadre deployment is indeed unlawful in the circumstances of the case.

Unqualified cadre deployment has also resulted in very debilitating problems, particularly in the sphere of local governing, where in relation to service delivery there have been widespread political protests, examples of which are set out above, some of which have become violent and politically destabilizing.

The failure to deliver adequate services, like housing, is not because of the inadequacies of the Constitution and its Bill of Rights, with its provision for socio-economic rights, but the existing glaring lack of capacity, cadre deployment and corruption that has occurred with the government and administration of South Africa during the Zuma presidency.

Service delivery in relation to housing invariably involves two or possibly the three spheres of government local, provincial and national. This has to take place in terms of chapter 3 of the Constitution, dealing with Co-operative Government. This requires that there should be sufficient capacity in each of the relevant spheres of government. Civil servants with expertise and experience are essential. Fundamental change is required in this regard to ensure adequate service delivery by a competent civil servants and politicians. It is cogently submitted that the new Ramaphosa administration must take decisive and bold steps to bring about meaningful change in this regard in the interest of good and competent government.