Copyright : Re-publication of this article is authorised only in the following circumstances; the writer and Africa Legal are both recognised as the author and the website address www.africa-legal.com and original article link are back linked. Re-publication without both must be preauthorised by contacting editor@africa-legal.com

African Women Touch Lives with New Tech #ThisAintYourGranddaddysAfrica

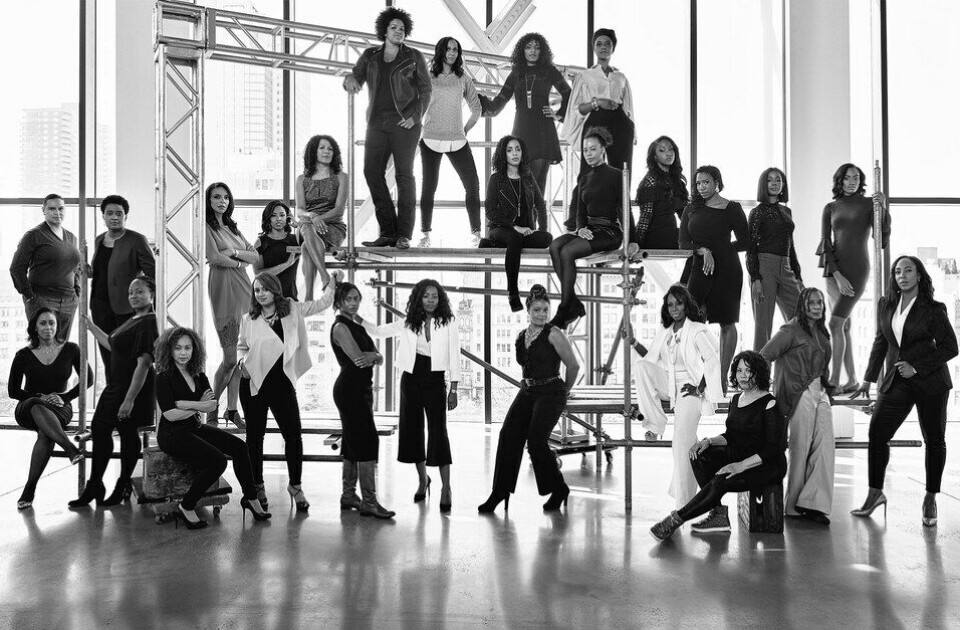

In April 2018 Vanity Fair published a photograph of 26 black women tech entrepreneurs based in the United States who had raised more than a $1 million for their companies. The photograph, by Mark Seliger who is known for celebrity portraits, is remarkable in that it reflects the united face of a demographic who have always been excluded from tech. In one room (yes, still only one room), is a power block of women who have made it to the top. And they are black; and several are rooted in Africa.

In the centre, shoulders back, eyes locked on the lens, with a confident half-smile is Viola Llewellyn, co-founder of Ovamba, a company that is changing the way business is done in Africa and already making meaningful inroads into alleviating poverty.

Llewellyn and her business partner, Marvin Cole, started Ovamba when they came up with a “leapfrog” solution to resolve the old problem of capital shortfall by enabling African SMEs to access money.

“We are a growth engine that enables investors, where there is a surplus of capital, to access Africa’s markets and earn good interest,” Llewellyn says.

In turn established small and medium-sized African business owners use their mobile phones using the app they created ‘Ovamba Plus’ to access this capital. Ovamba takes possession of the business’s incoming stock, enabling port clearance, logistics and warehousing and releasing stock when the business makes scheduled payments.

On delivery Ovamba provides a single invoice consolidating the total landed cost per item, effectively becoming a local supplier of product.

To-date approximately 260 businesses, mostly in Cameroon but now also in the Ivory Coast, have been helped with more than €144 million. Sudan, Ghana and Morocco are next on the list. The average transaction across the portfolio is about €85 200, but Ovamba can “lend” up to €500,000 to a business. Applications for funding take less than 5 working days and terms are between 4 and 6 months.

Llewellyn says the model is the first of its kind and fits with the African way of doing business, especially in the informal sector which has been ignored by banks.

“It means stock is always available, warehousing is paid and, in Cameroon’s major port in Douala, where there is massive congestion and backlogs because people can’t pay port clearance fees, containers are being moved on.”

Money comes through the capital markets in Japan, the United States and United Kingdom through vehicles like Crowdcredit. On the Crowdcredit website the Japanese company describes itself as a vehicle that “connects countries with funding gaps and countries with lending gaps on a global basis”.

One of Ovamba’s first supporters was the UK-based firm GLI Finance, whose backers include Blackrock Global, AXA Investment Managers and Barclays Wealth.

The tech is where Ovamba’s concept becomes very interesting. Risk, always an excuse for banks not to lend to the little person in Africa, is managed through algorithms that are tweaked to the exact specifications of a borrower’s circumstances. These algorithms take into account Africa’s diversity by including regional and cultural differences, geography and can even factor in tribe and a community’s attitude to authority and money.

“This is what banks do,” Llewellyn says, “Lenders in Germany look for different things in their clients to lenders in the United Kingdom or the United States. We are doing the same thing but with very regional knowledge.”

Too often Africa is seen as one homogenous mass, a hang-over of colonial thinking, Llewellyn says.

“There is very little sensitivity or knowledge about regional and cultural differences. Even within one country there are vastly different kinds of people with different attitudes to business.”

Young Africans are changing too, Llewellyn points out. “They are educated, driven and not confined to the old ways of doing business which depended on favours from the connected.”

Her recent hashtag #ThisAintYourGranddaddysAfrica trended on Twitter as young Africans acknowledged that the world they were creating would not be the same as their forefathers, so many of whom lived in suffering and servitude under colonialism.

“Africans are taking control of their lives and they have the ability to do so.”

Llewellyn, of course, is the absolute role model. Born to Cameroonian parents in the United Kingdom, she has always straddled two worlds. It is this understanding of how things work in the West coupled with an understanding of how things work in Africa that has her uniquely placed to find a mutually beneficial fit. While they grow Ovamba, she and Cole, a former senior associate of McKinsey & Company in Johannesburg, have based their company in Maryland in the US. “We understand what is important to African people – culture, tradition, language – and also how diverse the continent is. It is these things, coupled with an appreciation of the human factor that we have worked in to our business model,” she says.

In a recent interview with RFI, a French radio station, Llewellyn highlighted an example of a businessman who sold parts for motorbikes and cars and who was already on his fourth transaction of €500 000 . Since he began dealings with Ovamba his company’s growth had leapt by 450%. So staggering was his increase in turnover that his Moroccan supplier contacted Ovamba asking “Who are you people?”.

“We are African and what we are doing is using what makes Africa wonderful – being human with all its idiosyncrasies – to offer a new way to success and a better life.”

Going back to look at the Vanity Fair photograph one can’t help but feel a thrill for what these women mean for a changing world. Llewellyn’s legacy will be felt by the businesses her company supports for decades to come but also by the girls and women of Africa who see her do it

To view Vanity Fair, 26 Women of Color Diversifying Entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley, Media, and beyond click here

Join the conversation #ThisAintYourGranddaddysAfrica

Re-publication of this article is authorised only in the following circumstances; the writer and Africa Legal are both recognised as the author and the website address www.africa-legal.com and original article link is included. A bio can be provided on request.

Re-publication without reference to Africa Legal is not authorised.